THEIR FACES GLOW in the Manhattan sunlight, all the glorious queens, whether their wigs are hot pink or neon yellow, their eye shadow emerald or sapphire, their chins smooth or bearded. But refocus: Observe that boa they’re holding, all 1.2 miles of it, doubled back on itself again and again in a loose skein. Its dyed vivid hues clash, scream; the photos documenting its presentation on June 20, 2019, are a riot of color, texture, and form, like explosions in a craft shop. The men, women, and wonderful others brandishing this extravagant thing look triumphant, and so they should be—not because they have achieved a Guinness World Record for the longest-ever boa, but because they made it to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Queens like these were once forced to perform the best versions of themselves in the dark and danger of night. Now they can stand here, rainbow feathers in hand, proud and preening in broad daylight.

A long century ago in Britain, where I live, it was well-to-do women who were enamored with feathers, strutting and displaying with wings or even entire dead birds in their Victorian and Edwardian high fashions. Their feather frenzy propelled certain species around the world to the brink of extinction, and England’s exclusively male club of ornithologists did nothing. An all-female group of proto-conservationists stepped up, forming what is now the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to halt the “murderous millinery” killing off—all for the sake of hats—of hummingbirds, condors, and everything in between. The RSPB recently celebrated the centenary of its 1921 Plumage Act, which prohibits the import of exotic feathers and remains a monumental piece of conservation legislation.

But throughout history, humans have always used feathers to performative ends, and that certainly didn’t end in 1921. Sources and production have changed; in the West, at least, connotations have changed too: while feathered garments and accessories were once appeals to high status, since the late twentieth century they have first and foremost marked the look of camp. How did feathers in the Global North shift from serving aesthetic sensibilities of cisgender women to suiting those of queer men? And how will their role in camp culture change with broader ethical shifts that challenge our exploitation of birds and other animals?

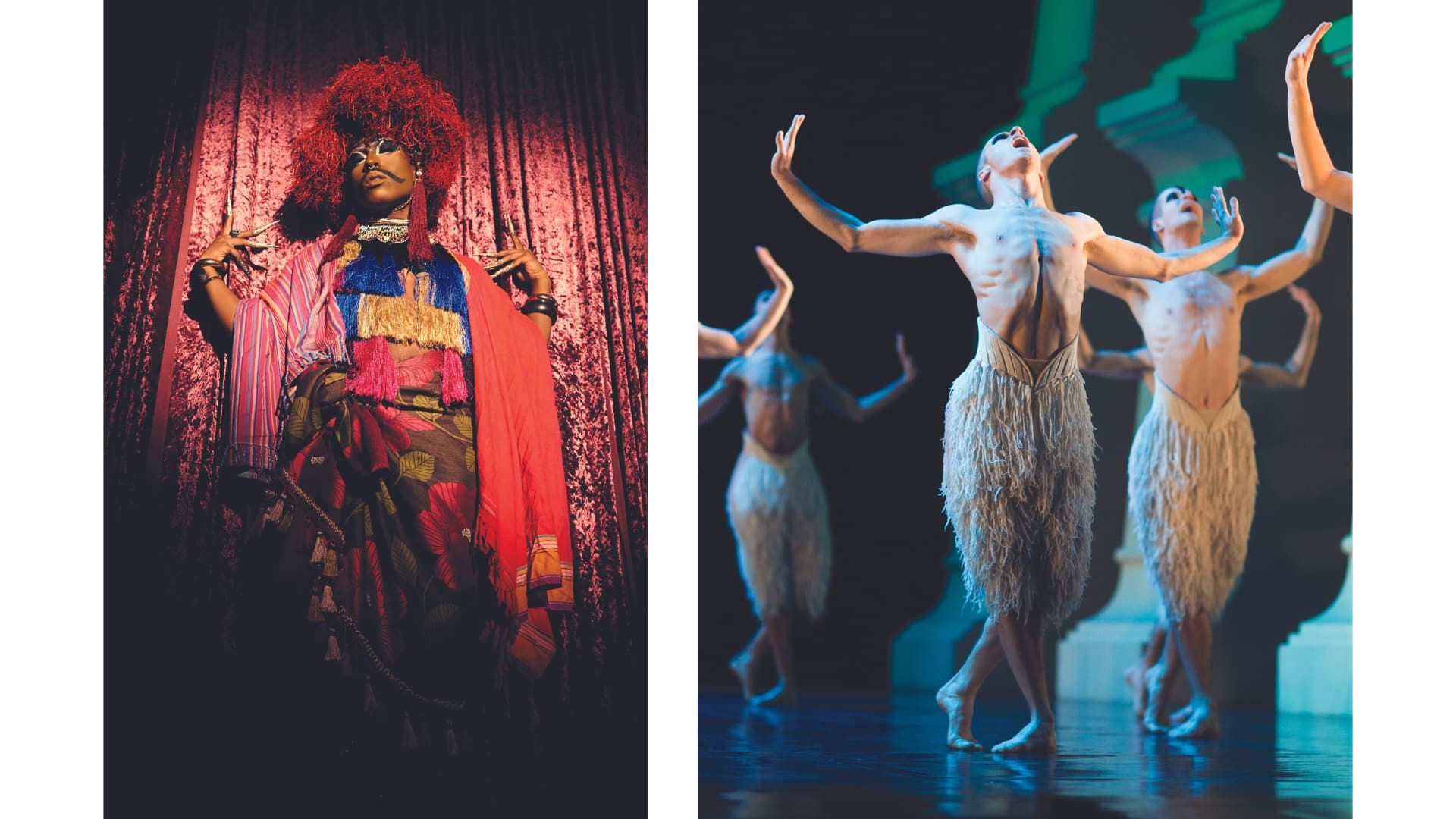

ALEXANDER MCQUEEN’S commanding golden feather jacket. Elton John’s carnivalesque feathered hat-mask. Matthew Bourne’s silk chiffon “feathered” breeches for his notoriously gay Swan Lake. “But these are all very male focused,” comes the disclaimer to a list of iconic references sent to me by Dan Vo, a museum consultant specializing in LGBTQ+ history. That’s the point, I chuckle to myself; boys have all the fun.

Sure, I’ve got pieces of my own: a skinny marabou boa of downy turkey feathers (used maybe three times in twenty-five years); a fascinator with faux pearls and a cockerel feather spray (topping off an outfit exactly once); a thick white turkey boa, a friend’s contribution to a queer cabaret evening (never used again). They are tucked away under the bed, shamefully closeted.

“Every human is jealous of birds,” the burlesque performer says.

Strict vegans aside, we all have our unwritten rules for what constitutes fair wear of animal products, based on some murky mix of convention, ethics, and simply what feels right. My own current wardrobe injunctions might draw some arbitrary lines—forbidding leather clothes and handbags, allowing leather shoes—yet they still feel meaningful for me. And while I am tempted by feathers, they remain contraband. It’s more than a matter of conscience, because it’s also avoidance of the macabre; I’m too viscerally cognizant of the bodies they were plucked from.

Adorning myself with feathers, moreover, feels irrelevant to me as a queer woman. I admit, I covet the sensuality of ostrich quills, the dazzle of peacock plumes, and I find them compelling mnemonics of the birds they come from. But wearing them, even in a pride parade or costume party context, signifies a brand of femininity that I don’t wish to signify.

Amanda Lawrence as The Angel; Andrew Garfield as Prior Walter;

Angel’s wings designers: Nick Barnes and Finn Caldwell.

(Photograph by Helen Maybanks)

However, I’m eager to learn what they mean, what they do, for some of my siblings under the rainbow umbrella.

Even if far less abundant than before, birds are ubiquitous. Observable, relatable, and diverse, they are easily ascribed with symbolic meanings, a sort of Rorschach test for human cultures. And when I listen to Anohni—the trans former frontwoman of Antony and the Johnsons—sing in such a longing, aching warble about transforming into a bird (because “bird girls go to heaven”), I sympathize with the powerful associations birds can hold for those born into male bodies who don’t subscribe to what’s typically expected of boys and men. I can imagine their yearning for the freedom and weightlessness that flight represents, and the sensual (feminine?) pleasure that being covered in feathers might yield. Regardless of gender and sexuality, don’t most of us long to spread our own true wings, freeing ourselves from the confines of social constructs? Don’t we all crave sensuous pleasure, unfettered from shame and fear?

Trash Valentine would agree. “I think every human is jealous of birds,” the burlesque performer says as we find seats in a northwest London pizza parlor (we were crowded out of his local pub due to bad timing with the European Football Championship, the domain of straight men). “And most people are jealous of performers for being able to put themselves out there and live that life. Embodying that onstage with feathers brings those two worlds together, and everyone enjoys it.” A Perth native, Trash Valentine was crowned Mr. Boylesque Australia in 2016 and now performs internationally. Although I’m meeting him out of character, I can easily envision his magnetic stage persona given his offstage charm.

Gay men have long felt at home in the theater and with theatricality. Add in the feathers, Trash continues, “and there’s a particular sex appeal, that showboating, like a peacock showing itself off.” One of his routines—a “quintessential burlesque performance,” as he describes it—involves teasing the audience with his implied nudity behind feather fans. In another act, he evokes the Las Vegas showgirl image, but because his costume uses bright yellow feathers, “everyone comments beforehand that I look like Big Bird. But it’s burlesque: it’s comedy, and that’s kind of the point,” he says. “And when I put on that headdress, no one in the room is able to ignore the six-foot-two man in a big yellow ostrich feather headdress. I like what comes with that; there’s the sense of power in getting that attention.”

Burlesque and drag, Trash explains, are about playfulness, fantasy, and refusing to be ignored, but also about validating a side of oneself that is not supposed to be expressed in polite society. They’re furthermore about the gender play, “whether using your own gender and exacerbating it, or portraying a gender different from your own.” Why do feathers fit so well into that? “It has something to do with the opulence of it all,” Trash thinks aloud following his shortlisting of gay culture referents: Marie Antoinette, Victorian fashion, and above all Kylie Minogue and her Showgirl tour, dripping shamelessly in royal blue ostrich plumes. “But I’m not sure why gay men connect with it.”

“It’s interesting,” I offer, “that one of the first things you mentioned was male peacocks using their feathers to attract potential mates.” From peacocks to cardinals to birds of paradise, we so often imagine species in terms of their colorful, showy males, not the so-called drab females composing the audience. “Why is it now seen as feminine for people to wear feathers?”

“Male birds are always better looking,” Trash replies, as my heart silently breaks for the hens. “Yet we associate feathers with femininity. I don’t know why.”

IT WASN’T ALWAYS gendered that way. In Renaissance Europe, for instance, ostrich feathers and other plumes were instantly recognizable as symbols—and tangible spoils—of imperial expansion, worn by men wishing to project an image of worldliness and wealth. Feathers continue to feature in military headgear, from the showy bonnets of Scottish Highland regiments to simpler hackles used in uniforms around the world.

Among Indigenous American cultures, different feathers have different sacred associations, but all form bonds between the bird who gives, the person who receives, and the spirit of creation itself. Red-tailed hawks bestowed theirs upon warriors; crows supplied medicinal healers; blue jays gave girls their coming-of-age veils. Ceremonial uses of feathers continue to evolve, such as in the showy contemporary costumes worn in intertribal fancy dancing. Above all, feathers remain points of pride and honor that, like the non-native American flag, are to be handled with utmost respect. Access for ceremonial purposes is increasingly protected alongside conservation measures: for example, a federal repository collects eagle specimens for scientific study and to supply them to Native Americans, among the only members of the U.S. public permitted to possess bald and golden eagle feathers or other parts.

The place of feathers in Indigenous cultures, manifest in myriad traditions and with a range of gendered meanings, is its own vast research topic. Yet it overlaps with the subject within the Global North, where feathers’ histories are intertwined with colonialism and exotification—and then social constructs of gender and sexuality, themselves inextricably linked with histories of dominance and suppression. When marginalized LGBTQ+ people in the West reach for feathers as they strive for self-empowerment, is the act one of affectionate biomimicry? Or is it an accidental gesture of exploitative extraction?

My friend Philip Engleheart, a theater maker with a penchant for historical research, joins my quest to understand feathers in the camp context, and he comes armed with books from his library. Some of them are artifacts themselves, such as Peter Ackroyd’s Dressing Up: Transvestism and Drag from 1979, that Phil says he’s cautious to show his students because of its outdated language. But sitting on a park bench flipping through Dressing Up—as well as histories of burlesque, world folk dress, and hats, glorious hats—Phil and I tease apart the feminization of feathers over time. Tease: that’s the operative word, right? Discussing vaudeville and cabaret, Phil keeps raising his arms and making back-and-forth gestures emulating a slinky, sensual tease with a boa. “At what point,” I ask him, “did gay men look at these showgirls with their feathers and say, ‘That’s what I want?’”

Phil doesn’t have an answer, but he recalls how Josephine Baker once described the offstage Parisian vaudeville world as the first place she could simply be herself, un-othered. Perhaps part of the allure of the spotlight for LGBTQ+ people, and for people of color, is the general access it affords to performing arts culture—traditionally a space more accepting of difference and critical of social norms. For Baker, savoring the spotlight meant drawing on certain racial tropes that make us cringe today. When I see my sister Josephine (queer and mixed like me) in my mind’s eye, she herself is eye to eye with her cheetah, Chiquita; there is a visual implication in that famous photograph from the early 1930s of equivalence between two “exotic” creatures. And when Baker wore feathers onstage, they were nods to feminine opulence, but they nodded more to the tribal, the savage, the animal. Feathers take on different valences depending on the social identity of the body beneath the costume.

Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London, 2014.

Dance company: New Adventures; choreographer: Matthew Bourne; designer: Lez Brotherston.

(Photograph by Helen Maybanks)

And when men wear feathers onstage, there is already an expression of power—as Trash Valentine acknowledged—in choosing to adopt the feminine. The nature of that power is tricky. Flipping through Phil’s books, I see Ackroyd spelled it out clearly in 1979: “Drag parodies and mocks women; it is misogynistic both in origin and intent.” Have things changed much since then?

I pose that question to Simon Sladen, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Theatre Performance at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, who has researched the phenomenon of cross-dressing in panto from the Victorian era onward. “For many, the creation of the Victorian pantomime dame can be read as a marker of misogyny,” he agrees, “but drag culture requires a more complex definition.” Sladen talks me through female impersonators and drag divas over the past century and a half, showing me that “there are so many reasons why men might dress or perform as women. Can it be read as a controlling mechanism, or is it a sign of allyship? What is the intent and what is the reception? This varies depending on each specific example, performance, and audience.” I think about conversations with queer female friends about RuPaul’s Drag Race, in which we genuinely can’t answer these questions and aren’t sure whether or not we support the show.

“There seem to be two groups of scholarship,” Sladen continues. “One says drag is misogynistic because it’s done by a man, impersonating a woman in an overexaggerated way with the desire for audiences to be entertained and laugh. The other says it’s empowering because it shows kinship: you’re an ally, you’re not a threat, you’re celebrating women, it’s an act of empowerment and an opportunity to share that with an audience. And it’s interesting to note that queerness is celebrated in the drag community, while Victorian performers were heterosexual men—they had to be, by law.” In short, it’s complicated, Sladen concludes. It has evolved and is evolving, and it needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Feathers take on different valences depending on the social identity of the body.

There’s also the difference, I realize, between mocking women and mocking femininity as a cultural construct. Sladen talks about performers like Danny La Rue who, while drawing on the Folies Bergère-showgirl aesthetic, use feathers as “a comedic device to show excess and as a distraction technique” from male bodies impersonating female ones. Obscuring hard lines of the male form, feathers also “capture and extenuate the motion of swaying hips” that are associated with women, even though it’s usually male birds who perform dancelike plumage displays. Sladen describes how Douglas Darnell—dressmaker for the likes of Shirley Bassey, Joan Collins, and Marlene Dietrich—defined the optics for female divas who became icons in gay male culture: It’s a look employing light-catching sequins and motion-enhancing feathers. In a way, this diva aesthetic satirizes sensual femininity, but not at the expense of women themselves. Further, when women go over the top in such a way, it’s not drag, but it can be that sort of excess we think of as camp. That’s exactly how Susan Sontag explained it in her 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” in which she likens the phenomenon (somewhat gruesomely) to “a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.”

For Trash Valentine, one necessary component of contemporary burlesque is satire. Pushing myself to watch a Drag Race episode where the runway category is feathers, and expecting mainly Dame Bassey-inspired robes and gowns, I see that RuPaul and his panel select a “Peak of the Week” whose satirical look flies in the face of expectation. They are not wowed by the pursuit of elegance, such as The Vixen’s 1920s-inspired number with an asymmetrical peacock train; they dismiss extravagance, like Monique Heart’s gold-dipped white feather cape; they are unmoved by melodrama, as in the three Goth homages to Maleficent complete with raven props. Instead, the judges opt for the absurdity of Asia O’Hara’s Tweety Bird costume, a loose yellow poncho with cartoon sequin eyes. Its ostrich plumes flop and flounce as Asia works it on the runway to the judges’ laughter. This instance of drag is not about becoming woman but about becoming bird—but not even an actual bird, only an animated caricature of one.

ASIA O’HARA’S Tweety is supposed to be a laugh. Maybe it’s even a commentary on the hackneyed use of feathers in these contexts, or a parody of people’s avian aspirations in general. Like birds, we LGBTQ+ people face real threats, locally and globally; there must be some solidarity there. Am I taking the Tweety act too seriously in reading it as a mockery of birds? But perhaps the same enlightened rules from comedy should also apply to drag: It’s funny when you’re punching up, not down. Not when you’re a human being punching down at a class of animals, and especially not when you’re wearing a costume made of products pillaged from those very same animals.

“To be honest,” I’m told by Toby Hawker—a former dancer, costumer, and producer on the elite international cabaret scene—“feathers are slowly dying out because of the movement against animal cruelty.” Hawker never wore them himself, but he helped transform many a female performer into an opulently winged showgirl. It used to be all about the ostrich, he says, and echoes Simon Sladen in describing sensuously rippling ostrich plumes as “extensions of the girl.” They’re also easily dyed and extra lightweight, materially well suited for the enormous, vibrant headpieces and “backpacks” whose wow factor justifies, in the audience’s mind, the price of their hundred-euro tickets. However, as environmental and animal awareness grows, designers are increasingly turning to feathers from domestic fowl, seen as less extravagant because at least they are industry byproducts. The prestigious Lido de Paris cabaret, Hawker explains, now only uses products from chickens and roosters in addition to peacocks, who shed their feathers and are not killed for harvesting. “Especially if a company is on the world stage,” he says, “if they’re using feathers that aren’t sourced properly, people will simply walk out the door.” Hawker has also helped produce shows using only foam feathers, which he claims look just the same from the audience’s perspective.

For London-based burlesque performer and former stylist Rudy Jeevanjee, whose veganism pushes him to consider his environmental impact onstage as well as off, avoiding animal products in his costumes has become a design challenge that affords exciting solutions. I found him on Instagram with a stunning red ostrich headpiece—which, when I looked closer, turned out to be something else entirely. “I was initially going to do a feathery thing,” he explains of this signature piece, “but then I had that conversation with myself: What can I make that is different? I decided I’d try straw. It gave me that feathery, flowy feel I was looking for. We don’t necessarily have to use feathers.” It’s not about tricking the audience by making faux feathers seem real, but about creating similar desirable effects through different means.

Rudy continues to wear items he acquired prior to his shift to veganism, particularly a black feathered collar that he layers with African beads. Of Barbadian heritage himself, many of his looks tap into non-Western aesthetics. He has reflected on the ritual usage of feathers in African and Native American cultures, although he hasn’t encountered many burlesque performers of color drawing on such traditions. Instead, the European cabaret tradition has engendered its own rituals surrounding feathers for performers of any background, and Rudy is still figuring out how to navigate them. “I don’t want to step on people’s toes,” he says with the deference of a relative newcomer and the humility of a gentle, thoughtful soul. “These are people with traditions who have been in this industry for twenty or thirty-plus years. Feathers are a very prominent part of the burlesque industry, and I’m a part of that. So I do what I can do. It’s nice to appreciate the glitz and glamor of the plumage,” he goes on, “but for me, anyway, is it ethically worth doing? I’m still working my way around how I personally engage with that.”

Left: Vocalist, dancer, and actor Rudy Jeevanjee. (Photograph by Stefano Della Salda)

Right: Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London, 2014.

Dance company: New Adventures; choreographer: Matthew Bourne; designer: Lez Brotherston.

(Photograph by Helen Maybanks)

In the meantime, Toby Hawker tells me, so many ostrich feathers are in circulation in cabaret that they continue to be reused. Maintaining them involves expensive backstage rigging to carefully remove performers’ backpacks and hang them high up, keeping them dust-free. “Feathers give me so much anxiety!” Hawker exclaims dramatically. He once saw a dancer fired on the spot for carelessly snapping a long headdress quill, and he sympathized with the managers: “If you don’t have respect for these feathers, you don’t deserve to wear them.” A production company he worked with recently is moving away from feathers in rental costumes for both ethical and practical reasons, as they’re so easily dirtied and damaged, difficult to repair and replenish. He talks me through alternative materials, including foam and tulle, that might achieve the same wow factor as delicate, dodgy ostrich plumes imported from South Africa.

But with every synthetic, Hawker cringes. “I can sense from the face you’re making,” I say through our video call, “that something is lost when you’re not using the real thing.” We explore the opulence (that word, again and again) that is an objective itself in his performance world; he gives me his own shortlist of feathered icons beloved by the gay community (Audrey Hepburn is his own number one). He describes the universally gay symbolism of the peacock—the bird Hawker identifies with, despite his bird-of-prey surname. He becomes most rhapsodic, however, when narrating his exhilarating, humbling, real-life encounters with sulfur-crested cockatoos and rainbow lorikeets in Sydney, where he has lived. “I’m just so into birds,” he gushes in a way that makes me almost fall in love with him, “and to be honest, it comes from going into the showgirl world, where they’re trying to be birds.” It’s an interesting trajectory.

I think back to the pizza parlor, where I had asked Trash Valentine whether aesthetic and social values of feathers in performance trump the ethical concerns. “When I bought my feathers,” he answered, “birds themselves weren’t even on my radar; I hadn’t had those discussions.” Investing in ostrich fans was a ceremonial milestone for him in terms of advancing his art, and in terms of staking a serious place in the burlesque community. Now, like Rudy and Hawker, Trash is concerned about animal welfare and knows audiences are, too. “I have the fans now; I have the feathers. I don’t think I need to throw them away to prove a point. But I do think it’s smart we’re having these conversations and deciding if it’s worth it, and what our artistic integrity is worth. Is it having the feather fans that makes you legitimate, or is it the value of your performance, even if your fans are made of tulle? It’s a matter of trying to reconcile that with your pride, as well.” Listening later to our interview, I notice the music playing in the restaurant as we’re talking about how feathers conjure up romantic notions, for audience and performer alike, about femininity, flight, freedom, and becoming bird. I laugh at the coincidence: clearly audible in the recording is “I Wan’na Be Like You” from The Jungle Book, a song about the comedy and the dangers of interspecies envy.

MY BROWSER TABS are full of references the boys have mentioned, images that have—increasingly, surprisingly, in spite of myself—stirred in me a jealous longing. I find myself falling for Audrey Hepburn in a powder blue pillbox hat: its dramatic feather waterfall is stripped of barbs except at the tips, which gently graze Audrey’s forehead and frame her liquid eyes. And Alexander McQueen’s feathered jacket looks like a gold-leafed mythological figure, a sculpture from a missing page of classical art history. I imagine the feel of those feathers on my own skin, the costumes on my body, the sensuality and power and freedom they would bring.

Instead, my body is stuck at a desk (is it a beautiful coincidence or a cruel tease that my shared studio is in Peacock Yard?). While writing this, my family is limiting our activities rather conservatively in pandemic times, so I daren’t attend performances for this research—even conducting one interview in a restaurant feels reckless. Completely out of the question is a long train journey to observe ostrich plumes in situ on wings and rumps of actual live birds, but that doesn’t stop me googling “ostrich farms UK” every few weeks.

Nor can I visit the Natural History Museum in person. But I can Zoom with Alex Bond, the museum’s senior curator in charge of birds. Feathers on queer catwalks are a step removed from Bond’s professional focus—conservation of marine birds—but I’m eager to talk with him as a recipient of the Royal Society Athena Prize for advocating LGBTQ+ diversity within the sciences. He is thoroughly versed in the history of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds as having stemmed from objections to feathers in fashion: he helped curate a virtual exhibition on the centenary of the Plumage Act, and he has a number of its objects at hand. He holds up an egret feather duster, and I gasp, incredulous. Hundreds of wispy plumes float across my screen. They taunt me because I can’t reach out and touch them; they make my stomach turn at the senseless carnage they represent. Egrets were among the Plumage Act’s main success stories, as the birds’ calamitous decline was reversed after they could no longer be imported. “It’s beautiful and horrifying at the same time,” I murmur.

“Welcome to conservation biology,” Bond says with a grimace. He shows me hundred-year-old grebe pelts from South America, probably intended to become ladies’ muffs. He has whole hummingbirds from the 1880s and ’90s wrapped in bits of newspaper from the time, ready to be sold for hats. He mentions he can access hundreds of thousands of bird specimens with the keys in his pocket. It’s all rather grim.

Don’t we all crave sensuous pleasure, unfettered from shame and fear?

Feathers worn today by drag queens and burlesque performers beg ethical questions, but they don’t represent conservation concerns, which are Bond’s primary interest. “In the grand scheme of things, feather boas are pretty low down on the list of environmental impacts we have at the moment,” he says. Of course, I agree. I blush, self-conscious about the triviality of my research in the face of his. But I push myself to recount my conversations with queer performers and designers for whom feathers hold so much aesthetic and social value, for whom they carry nuance and summon ambivalence, for whom they play ritualistic roles onstage and off, for whom they bespeak status and belonging.

Bond lights up. “It’s the same with birds,” he says, animated. “That’s why they have these fantastic ornaments. The bigger your crest, the better your quality as a mate. It’s interesting to see that parallel. Feathers are energetically very expensive to produce—some don’t benefit your survival, and in some cases might even hamper it. You’ve got to have a certain level of fitness to be able to make them and use them. So clearly you must be good, if you can do all of this.”

I’m pleased it’s a (gay) biologist who completes the analogy for me. And with such joy.

“‘HOPE’ IS THE THING WITH FEATHERS—” wrote the probably-maybe lesbian or bisexual Emily Dickinson, with insistent dashes like incredulous gasps (did she see egrets, too?), “That perches in the soul— / And sings the tune without the words—/ And never stops—at all—” It’s a lot to ask of Dickinson’s little songbird to represent a monumental concept such as hope.

I look again at the New York drag queens with their record-breaking feather boa, measure the distance between Times Square in 2019 and Stonewall Inn in 1969, between the Stonewall riots and puritanically repressive Amherst, Massachusetts, where Dickinson would have penned her inspiriting poem in 1862. If only Emily and her beloved Susan could stand, hand proudly in hand, alongside those bright queens in full display. They would see that, yes, it is hope, throughout the years, that brings us forward, but it is also a lot of damned hard work in the face of violence and condemnation. A few feathers here and there might make it all a bit more bearable.

This piece is from Orion’s Winter 2023 issue, Romance in the Climate Crisis. Special thanks to the NRDC for their generous funding of this issue.