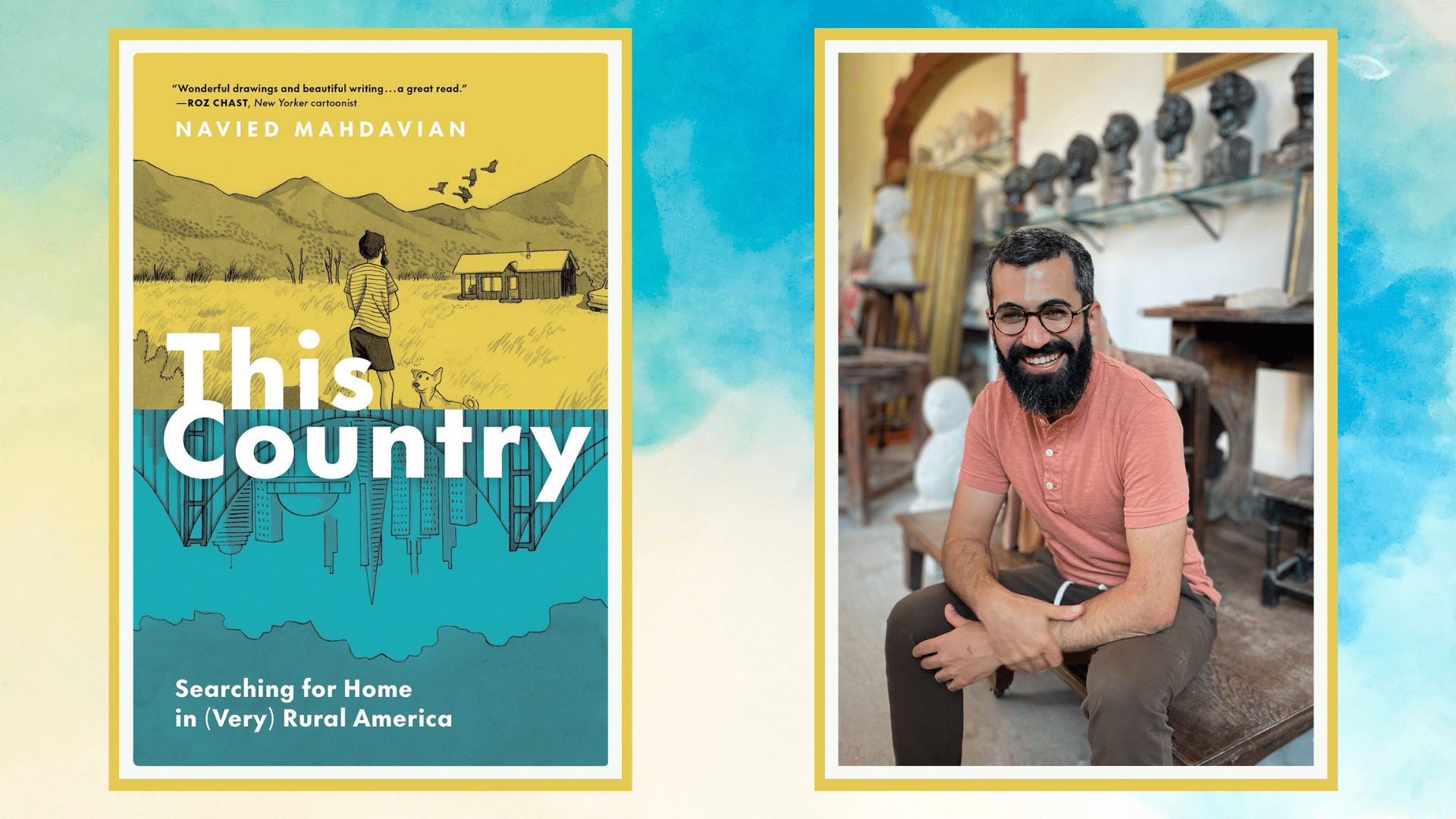

BEFORE IRANIAN AMERICAN cartoonist Navied Mahdavian moved with his wife and dog from San Francisco to an off-the-grid cabin in rural Idaho, he had never fished, gardened, hiked, hunted, or lived in a snowy place. But there, he could own land, realize his dream of being an artist, and start a family. Over the next three years, Mahdavian leaned into the wonders of the natural landscape and a slower pace of living. But beyond the boundaries of his six acres, he was confronted with the realities of America’s political shifts and forced to confront the question: Do I belong here? Navied sat down with Orion’s digital editor Kathleen Yale to discuss identity, place, humor, naiveté, and his new graphic memoir, This Country: Searching for Home in (Very) Rural America.

Kathleen Yale: The visual imagery in This Country is beautiful. There is a softness, an almost whimsical intimacy in the way you draw landscapes, flying bats, migrating birds, moon shadows, and wild tracks in the snow. Your love of the land around you is evident. Was this kind of drawing something new for you, or do you often lovingly sketch two-headed calves and birdbaths?

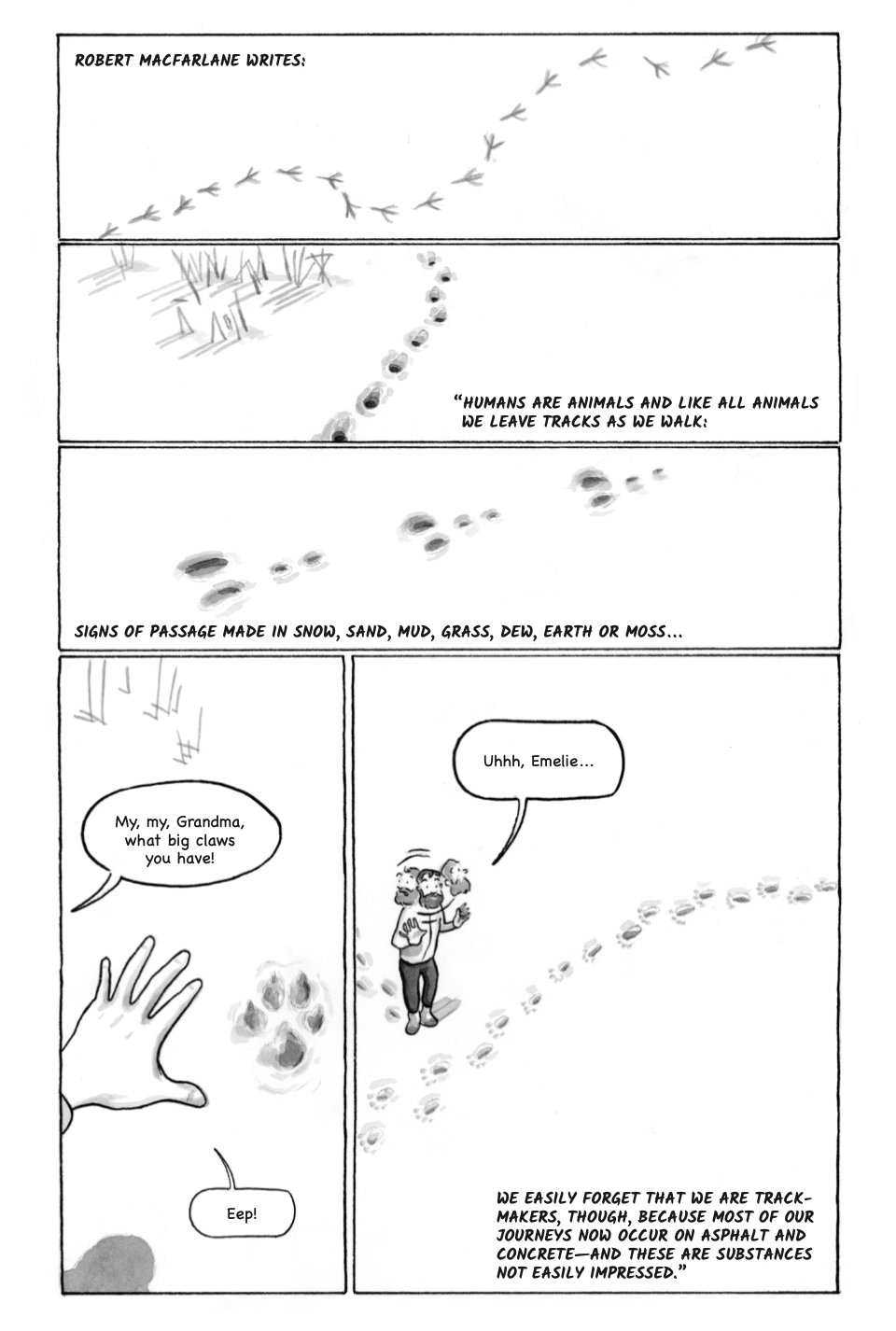

Navied Mahdavian: Most of my drawing at the time was cartoons, frequently of dog butts, which I do draw lovingly. My love of the land was something that developed over time, and in many ways, is specific to that land and that time. I am not usually the outdoorsy type and prefer to appreciate the landscape from inside my climate-controlled apartment. But the land is maybe the central character of the book, so developing a visual vocabulary to express it was important and new to me. In his book The Lost Words, Robert Macfarlane writes about how easy it is to miss things in the natural world when we don’t have words for them. We literally cannot see them. By the time we left Idaho, I could track seasons by birdsongs. Learning to draw these birds for the book only deepened my love of the place. I had initially intended to write the book as an almanac, but everyone quickly (and correctly) pointed out that people want characters and not just birds (wild, I know). But I knew I still wanted to include extended sequences of quiet visual imagery. And there is something so wonderfully meta about drawing tracks because drawing is itself a type of imprinting, just on the page instead of on the land.

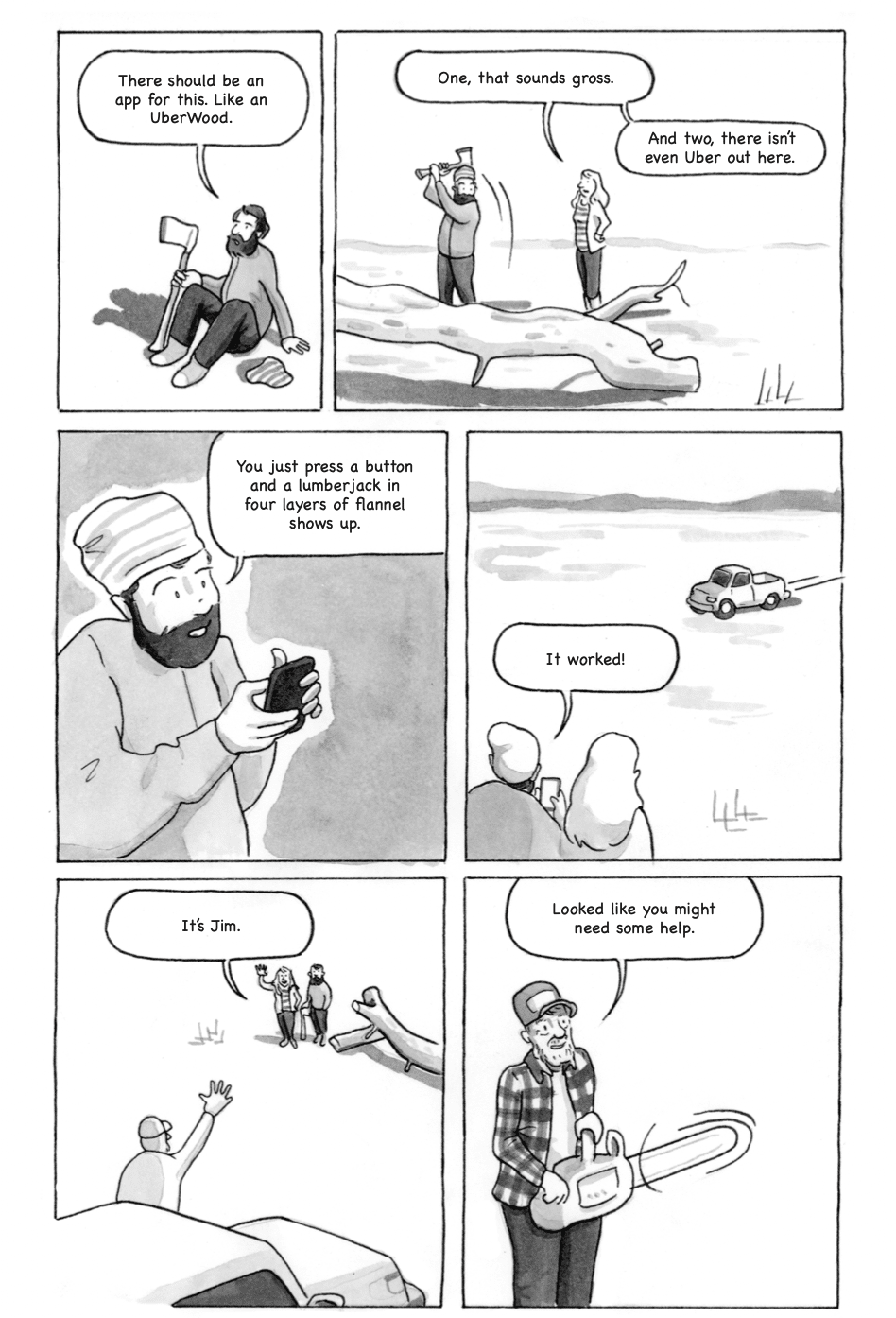

KY: There is such playfulness in your work here, too. I found myself smiling a lot while reading it. Are you this funny in real life?

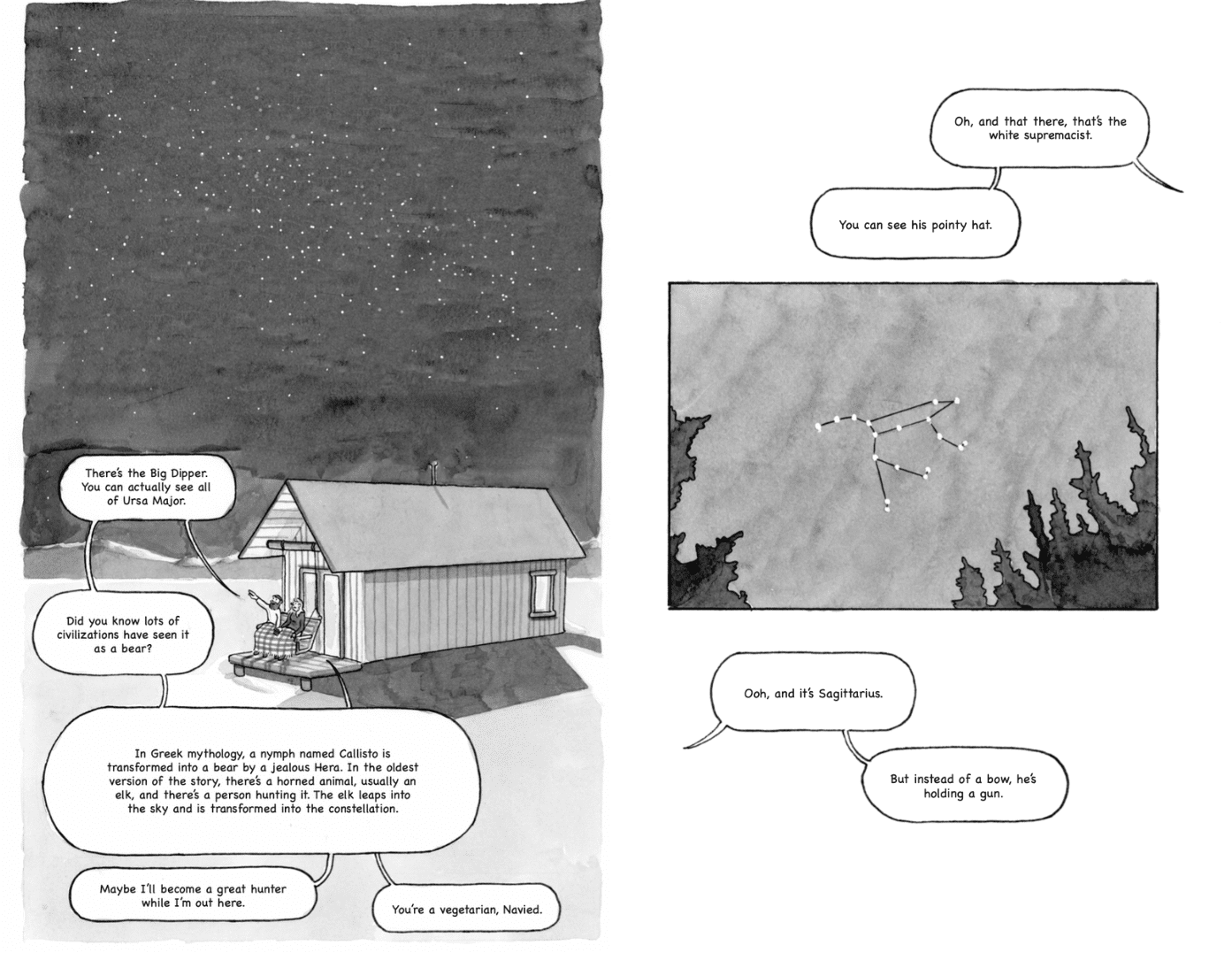

NM: Yes!—if you ask my mother (very handsome too!). I like to think I am funny in real life, but I definitely played up the humor for the book. It’s easier to critique something—in this case, aspects of the culture of the town—if you’re self-deprecating, so I leaned into the bumbling idiot persona, which wasn’t too much of a stretch (see, I can’t stop!).

KY: So is the Navied in this book an accurate portrayal of the Navied who created the book, or more of a character enlisted to guide the story?

NM: In many ways, yes. I think friends and family would recognize the Navied in the book as the Navied they know. But he is also a character that I had to create to tell a story, which is a process I imagine many memoirists contend with. There is a constant conversation between your lived experience, which is the source of the material, and the need for the story arc to edit and refocus. As I reflected on book Navied, I saw myself in a new light. When you’re doing your best, you don’t always feel like a bumbling idiot, even if that is the way that you look.

KY: I live in northwestern Montana and spend a lot of time in remote wild places, I am familiar with the political signs and bumper stickers on display in the rural West. I know how the best and worst of my state makes me feel. And I have to say, I’m just so impressed by your sense of adventure. Not that moving to rural Idaho is inherently adventurous, but building your own off-the-grid place from scratch with little experience to draw on was impressive to me … and intriguing. What lit that spark in you and your wife Emelie?

NM: When I started writing the book, the first question I had to answer was the “why” of our moving there, which was a lot more difficult than I would have imagined. Certainly, there was an element of romanticism (and spoiler alert: naiveté). We had visited the area on a whim the summer before and had fallen in love with the landscape and the freedom it seemed to promise. But there was also the practicality of the place: land was cheap and we could own a tiny home, an impossible prospect in San Francisco. Emelie is the practical one (also capable and smart—I am the funny one, or at least that’s what I tell myself), so she designed the tiny house and found Amish builders in the area to build it. We both wanted to be artists and we could do this living in an off-the-grid home, free from the pressure to work. As Virginia Woolf said, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” We may not have had money (and only one of us is a woman), but we had a room to write. And if we happened to meet a cast of kooky characters while we were there, all the better (see above: naiveté). In retrospect, it seems much more adventurous than it felt at the time, but maybe I’ve just blocked out my mother’s protestations and concerns for my safety.

KY: Were the relationships you formed there the type to persist across time and space, or were they more fleeting—important for a moment, in a particular place?

NM: I think they were relationships of circumstance, specific to that particular moment and place. But I don’t think that diminishes their significance; I carry that experience with me. Things are only more divided than they were in 2016 when I moved there. I try to remember these unlikely friendships when I can’t make sense of the other half of the country.

KY: You sell your cabin at the end of the book. Have you been back to visit that area since?

NM: I haven’t. I recently learned that the cabin was torn down by the new owners. They’re currently in the process of building a much larger home and an RV barn. Soon, they will fence cattle in. If there were an epilogue to the epilogue to the book, it would be this—which feels fitting. In many ways, their vision is more in line with the dominant paradigm of the place. So much of my experience there was our tiny house. I chose to end the book with an image of the house for this reason, to give it the last word, as it were. I’m not sure what it would be like to visit the place without it. It feels like a death of sorts.

KY: Ah, that’s a bummer. I wish more people wanted to live on the western landscape in that way. Now that you’re back living in a city, what do you miss most about your years at the cabin?

NM: Time. And the experience of it moving slowly. I grew up in Miami and spent my 20s in the San Fransisco Bay Area, so seasons are not something I was accustomed to when we moved to Idaho. And the seasons there are extreme. Something I explore in the book is how the land operates on the body. I wasn’t familiar with the names of the moons before I moved there, but after some time, I intuitively understood their significance. June is the strawberry moon because it is time to harvest strawberries. February is the hunger moon because you have used up your stores from the previous year’s harvest. There is a way we are meant to be in the world. It was nice to experience that for three years. Cities have a way of flattening time and space. It is always bright. One is always harried.

KY: The book ponders what it means to belong to a community, to a country (both a local landscape and a political body). Where do you belong?

NM: I’m a millennial. Not knowing where we belong is our thing. In some ways, I do know I don’t belong in (very) small-town America. Despite having lived in a town of 500 for three years, I couldn’t escape the tug of the outside world. I think it is particularly hard to escape this pull as an artist. Art needs an audience, so even in my tiny cabin, I had to orient myself outward. Being a New Yorker cartoonist, that audience was usually in bigger cities (“East Coast humor,” as someone in town called it). But I learned a lot while I was there, like the ethos that is particular to small communities. It’s not a new idea that cities are alienating, but it’s hard to truly get that until you’ve lived in a small town and experienced the charity of neighbors. There were also moments of alienation there. But I hope I will carry a little of the good I experienced there with me as I continue to search for where I belong. Because in the end, we’re all just trying to figure out who the hell we are and what the hell is going on.

KY: What other graphic novels would you put on a shelf next to This Country? What other cartoonists do you feel you’re in particular conversation with? (Kate Beaton’s Ducks came to mind immediately.)

NM: Ducks is brilliant. I feel like any conversation between Kate and me would involve lots of head-nodding on my part. I loved Joe Sacco’s Paying the Land, which deals with the land and our relationship with it. There are so many great cartoonists dealing with issues of identity and migration like Mira Jacob’s Good Talk and Malaka Gharib’s I Was Their American Dream. And as an Iranian-American cartoonist, it’s hard not to immediately think of Marjan Satrapi and Persepolis (the yardstick by which all graphic novels are measured, in my opinion).

KY: Ah, yes, good company. I think you fit right in. Thank you, Navied.

Order your copy of This Country today!

Navied Mahdavian has been a contributing cartoonist at the New Yorker since 2018. His work has also been published in Reader’s Digest, Wired, and Alta Online and the books The Rejection Collection and Send Help! Before becoming a cartoonist, he taught the 5th grade where he learned most of his jokes. Navied was born in Miami and lives in Salt Lake City, Utah with his wife, a Sundance-award winning filmmaker, and their daughter.

All images are from This Country by Navied Mahdavian. Copyright © 2023 by Navied Mahdavian. Reprinted by permission of PA Press, an imprint of Chronicle Books.